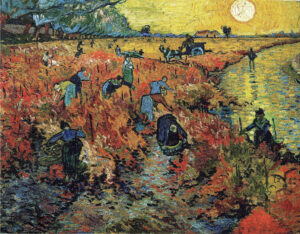

If asked about your favorite dish, you’d do well to name something exotic. Gone are the days when a taste for the likes of Italian, Mexican, or Chinese cuisine could qualify you as an adventurous eater. Even expeditions to the very edges of the menus at Peruvian, Ethiopian, or Laotian restaurants, say, would be unlikely to draw much respect from serious twenty-first-century eaters. One solution is to take your culinary voyages through not just space but also time, seeking out the meals of centuries and even millennia past. This has lately become somewhat easier to do, thanks to the work of Harvard- and Yale-associated researchers like Gojko Barjamovic, Patricia Jurado Gonzalez, Chelsea A. Graham, Agnete W. Lassen, Nawal Nasrallah, and Pia M. Sörensen.

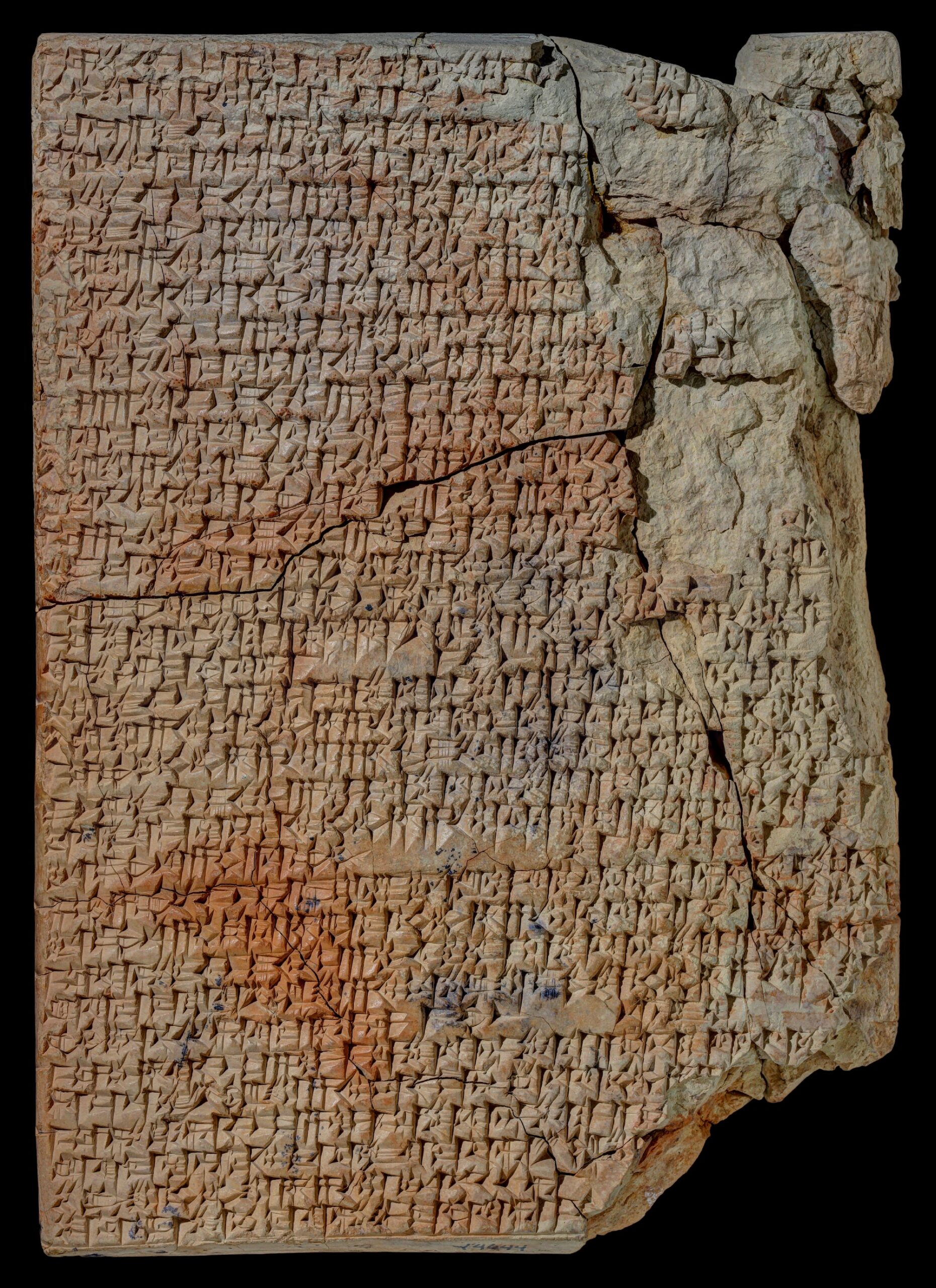

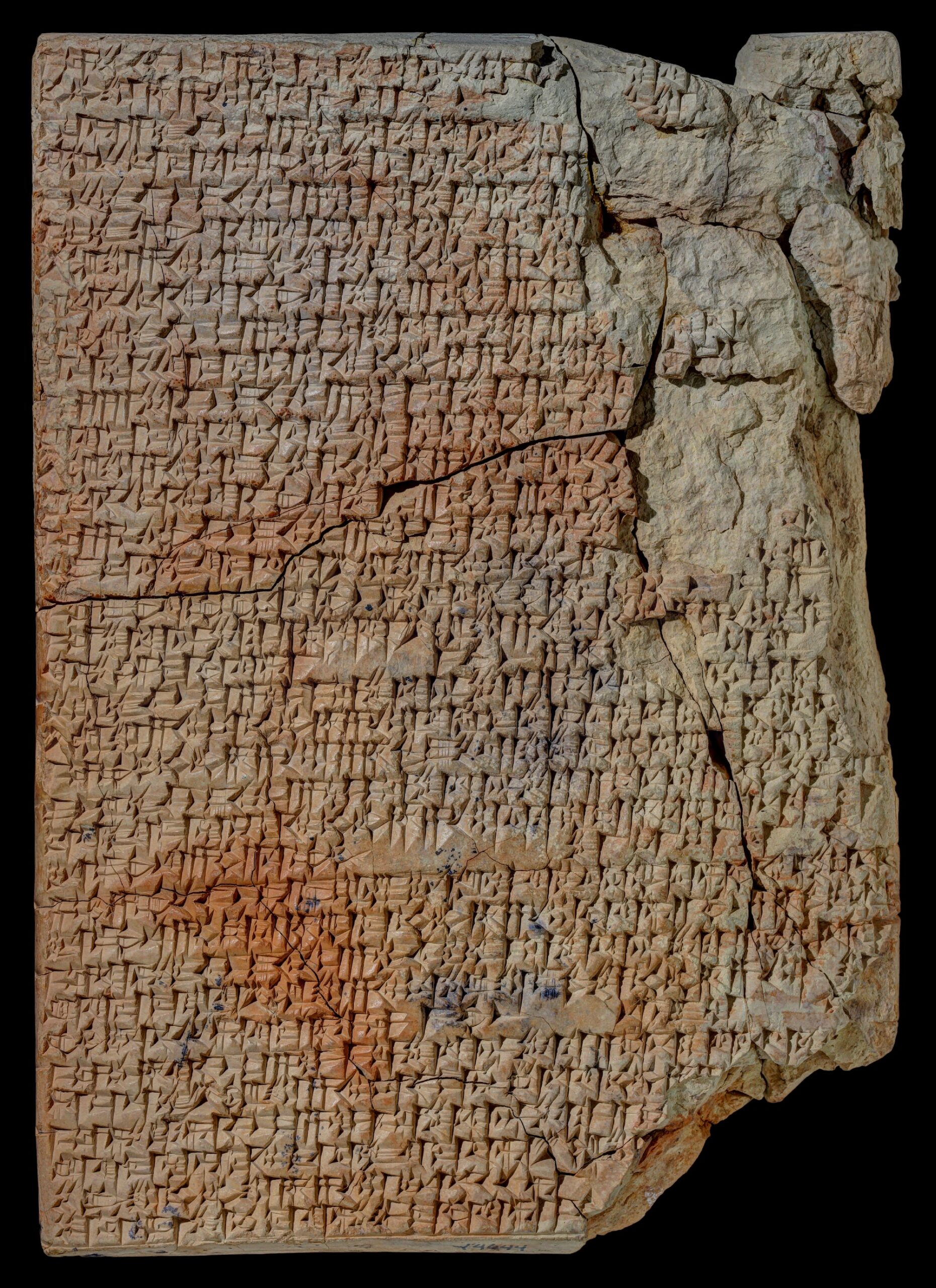

A few years ago, that interdisciplinary research team participated in a Lapham’s Quarterly roundtable on making and eating the ancient Mesopotamian recipes contained on what are known as the “Yale Culinary Tablets.” Dating from between 1730 BC and the sixth or seventh century BC, their Cuneiform inscriptions offer only broad and fragmentary guidance on the preparation of once-common dishes, none of which, luckily, are particularly complex.

The vegetarian soup pašrūtum, or “unwinding,” involves flavors no bolder than those of cilantro, leek, garlic, and dried sourdough. The stew puhādi, which uses lamb as well as milk, turns out to be “delicious when served with the peppery garnish of crushed leek and garlic.”

The Yale Culinary Tablets reveal that the Babylonians, too, enjoyed tucking into the occasional foreign meal — which, four millennia ago, could have meant a bowl of elamūtum, or “Elamite broth,” named for its origin in Elam in modern-day Iran. Another dish made with milk, it also calls for sheep’s blood (“the mixture of sour milk and blood may sound odd,” the roundtable article assures us, “but the combination produces a rich soup with a slight tartness”) and dill, which seems to have been the height of exotic ingredients at the time. Tuh’u, a leg-meat stew, has an identifiable descendant still eaten in Iraq today, but that dish uses white turnip instead of the ancient recipe’s red beet. Given that “Jews of Baghdad before their expulsion used red beet,” it’s “tempting to link the recipe to the continental European borscht.”

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Reconstructing these recipes, which tend to lack quantities or procedural details, has involved educated guesswork. But no other texts in existence can get you closer to reconstructing ancient Mesopotamian cuisine in your own kitchen. If you’d like to see how that’s done before giving it a try yourself, watch the videos above and below from Max Miller, whose Youtube channel Tasting History specializes in preparing dishes from earlier stages of civilization. Not that departure from the recipes as originally dictated by tradition would have any consequences. Most of these recipes may date from an era close to the reign of King Hammurabi, but there’s nothing in his famous Code about what happens to cooks who make the occasional substitution.

Related content:

Cambridge University Professor Cooks 4000-Year-Old Recipes from Ancient Mesopotamia, and Lets You See How They Turned Out

Watch a 4000-Year Old Babylonian Recipe for Stew, Found on a Cuneiform Tablet, Get Cooked by Researchers from Yale & Harvard

How to Make Ancient Mesopotamian Beer: See the 4,000-Year-Old Brewing Method Put to the Test

How to Make the Oldest Recipe in the World: A Recipe for Nettle Pudding Dating Back 6,000 BC

Behold the Oldest Written Text in the World: The Kish Tablet, Circa 3500 BC

Tasting History: A Hit YouTube Series Shows How to Cook the Foods of Ancient Greece & Rome, Medieval Europe, and Other Places & Periods

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.